Back then, working class families being able to buy their own home was a novel idea. Construction booms, oil crises, ‘potato diet’ austerity measures and new patterns of consumption changed the everyday lives of Danes in the following decades – and also their perception of what was possible. Banks and mortgage credit institutions offered new loan options that made it possible for many to attain the “villa, Volvo and ‘vovhund’ (a dog)” ideal.

Women off to work

“Make good times better” was the Social Democratic slogan at the 1960 election. The slogan came on the back of the economic upswing that started in 1958 and was to prove a uniquely long period of expansion for the Danish economy.

Photos: In 1960, around 560,000 women were in work, 10 years later that number had grown to 830,000. Growth was particularly apparent among married women, where numbers doubled.

The upswing gave Danes more money in their pockets in the 1960s. This also coincided with a change in the division of labour in Danish homes. Previously, women had generally remained at home and taken care of the children, but more women suddenly began to keep working after they were married.

That was also the case with Lis Madsen’s family, when she in 1973 swapped being a housewife with working as a school secretary.

Apartments face competition

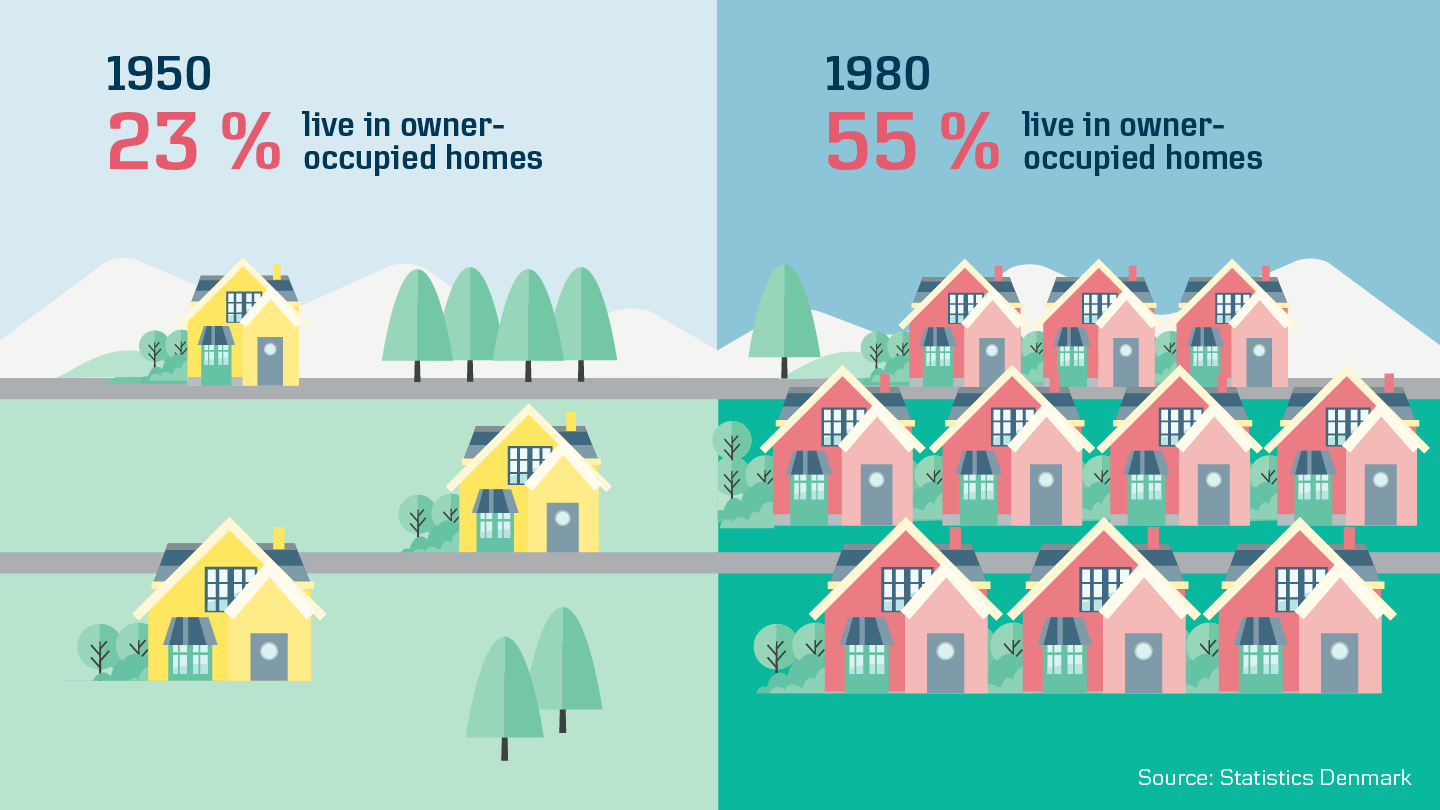

Women entering the labour market is often cited as one of the explanations for the surge in new private housing estates in the suburbs. The dream of having your own house and garden grew as Danes became increasingly well off. From the 1960s and for the next twenty years, several hundred thousand waged employees moved out of cramped rental property in the cities and into owner-occupied homes in the suburbs.

Reasons behind the boom in new private housing estates

Curt Liliegreen, Project Director at the Knowledge Centre for Housing Economics (‘Boligøkonomisk Videncenter’), here discusses the reasons for the boom in private detached housing estates in the 1960s and 1970s.

Workplaces were disappearing in the rural districts and being created in urban areas. This was one reason why new and very extensive estates with tower blocks and single-family homes (the so-called parcelhus) shot up in the suburbs in the 1960s.

Towns like Greve, Ishøj, Albertslund and Taastrup are just some of the suburbs that grew around Copenhagen at this time. In the Aarhus area, the same happened in Mårslet, Tranbjerg and Hjortshøj.

From field to suburb

On 15 October 1968, the then 32-year-old Lis Madsen moved to Dragør with her husband and two children. Landmandsbanken helped the family with a loan, so they could move into their own house. They were some of the first to arrive in the area, which since then has grown into a tightly packed neighbourhood.

More could have housing dreams

The growing middle class, which Lis and her husband were part of, could realise their dream of a single-storey house with help from a mortgage loan.

At the start of the 1970s, there were 24 different mortgage credit institutions in Denmark. To finance a home purchase, Danes needed to take out a loan with at least three different mortgage credit institutions. In 1970, the Danish parliament, ‘Folketinget’, passed a reform of the mortgage credit law that made it possible for more to realise their housing dreams.

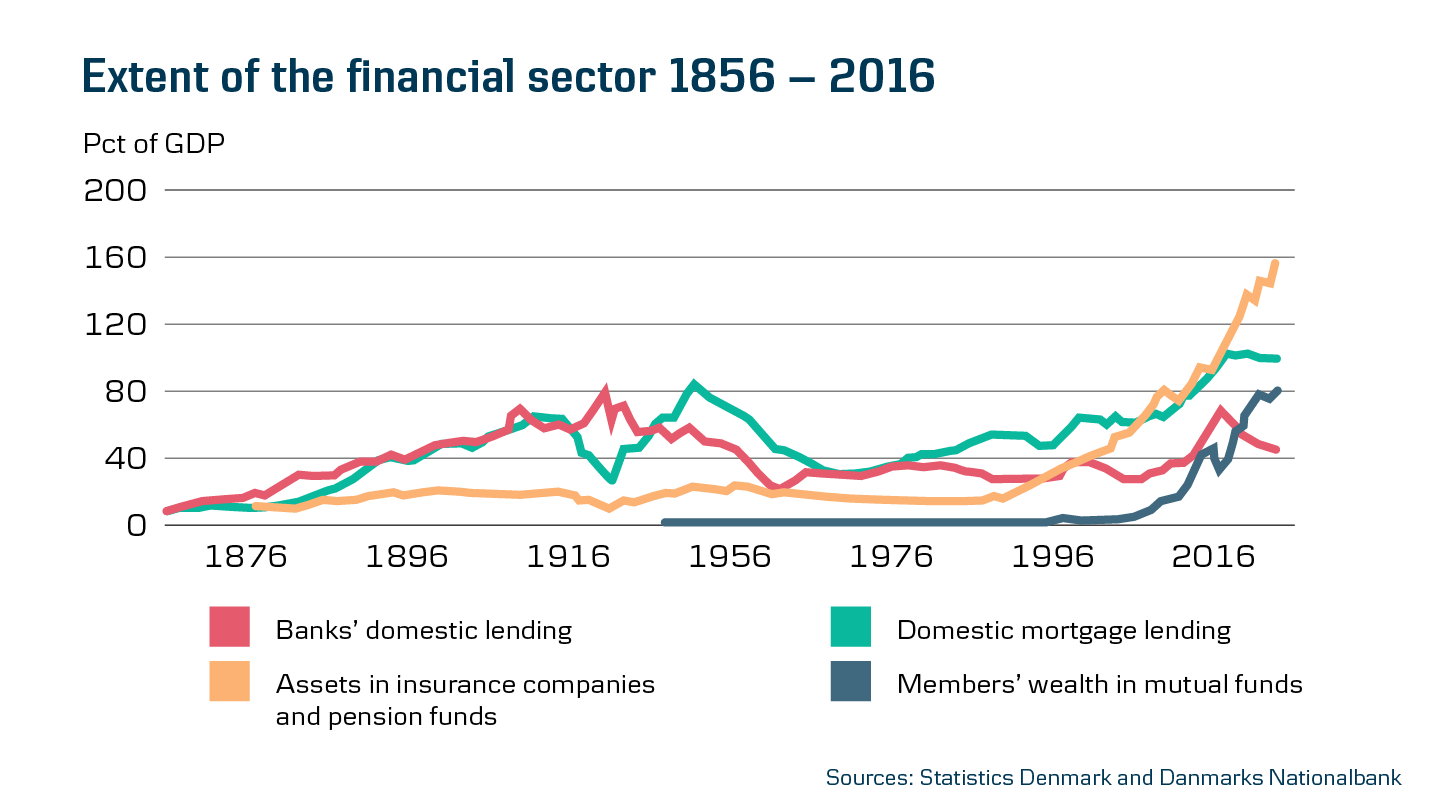

The reform reduced loan tenors and limits, and resulted in a string of mergers. Ten years later, Denmark had three general mortgage institutions: BRFKredit, Nykredit and Kreditforeningen Danmark, which later became Realkredit Danmark, now part of Danske Bank. Graphic: The mortgage credit loan has historically been an important element in relation to bank lending – and is currently the most important in Denmark.

Graphic: The mortgage credit loan has historically been an important element in relation to bank lending – and is currently the most important in Denmark.

Mortgage credit model ensured equal loan terms for all

The Danish mortgage credit model made it possible not only for the wealthy to move into owner-occupied property, but also working families.

Curt Liliegreen, Project Director at the Knowledge Centre for Housing Economics (‘Boligøkonomisk Videncenter’), explains how the Danish mortgage credit model differs from those in many other countries around the world:

Money for consumption and child savings accounts

Economic growth in the 1960s drove up both wages and inflation. As well as mortgage loans for homes, terms on consumer loans from the banks also became more favourable. Moreover, interest expenses could be deducted from tax.

With more money in their pockets, families could now acquire goods that had previously been viewed as luxuries. Hence, fridges, TVs and telephones went from being reserved for the well-heeled to becoming standard appliances in Danish homes.

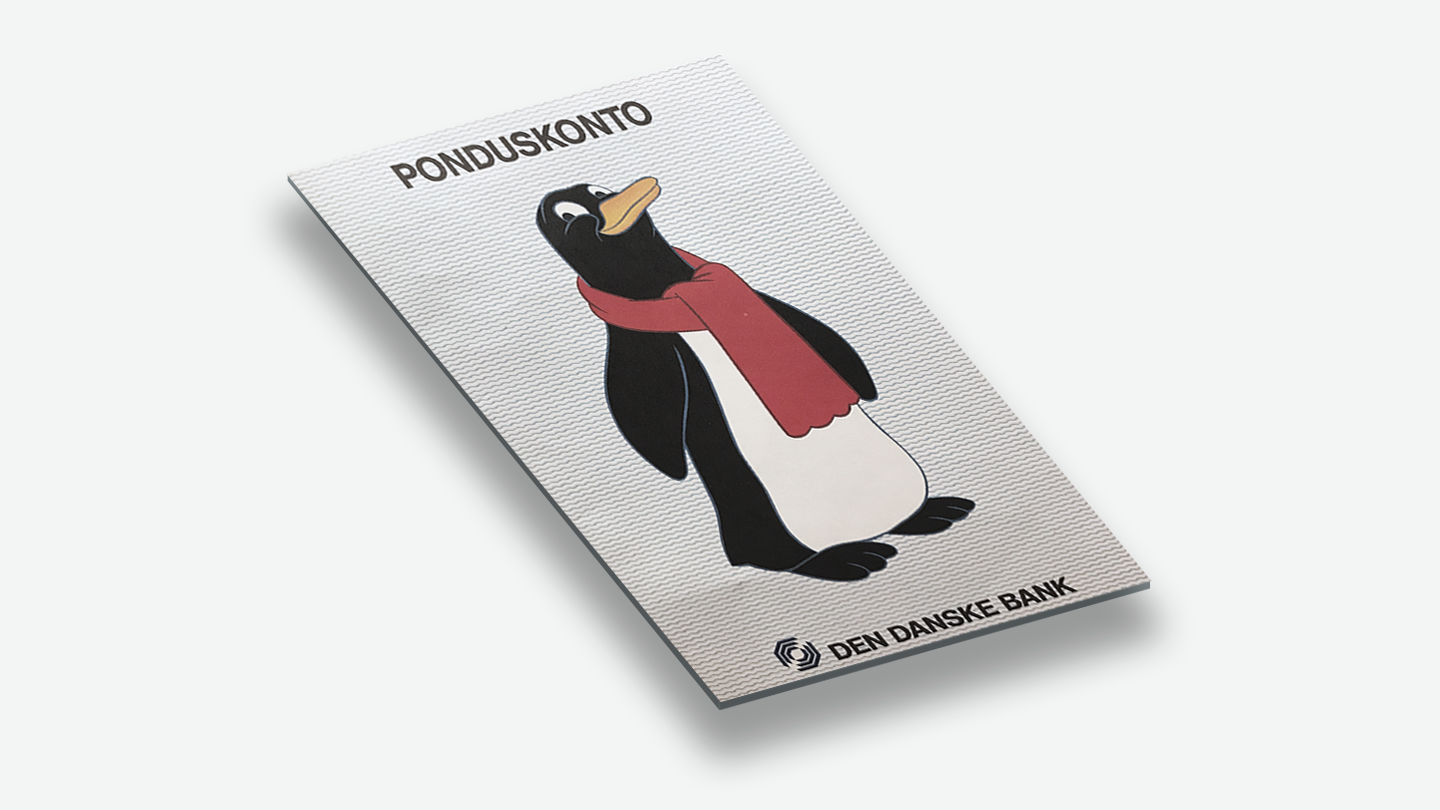

Children, too, got to share in this wealth. Landmandsbanken was the first in Denmark to launch a savings account for children. Along with the account came Pondus in 1968, the iconic ‘piggy bank’ – actually a penguin – which got its name from a penguin in Copenhagen Zoo that Landmandsbanken sponsored.

In the course of just six months, some 300,000 children across the country got a Pondus for saving up coins and banknotes. Pondus was a huge success. Ten years later, more than four million Pondus piggy banks had been produced.

However, a physical piggy bank no longer has the same prominent place in the children’s bedrooms in Dragør or the rest of the country. In Dragør, Lis Madsen’s great-grandchildren can now receive pocket money digitally with a swipe in Danske Bank’s pocket money app. Generally speaking, children have to learn that money is no longer physical, but digital.

.jpg?rev=3ab8996179834193a39aa2d43d971b43&hash=FF8F48CDB84714E34DB7F2F78E30721A)

Photo: Pondus being designed in Copenhagen Zoo in 1967.

Photo: Pondus in 1968.

Photo: Pondus after 2015.

Here, many years after the first boom, the ‘parcelhus’ remains the Danes’ preferred form of housing.

More than 3.2 million Danes live in an owner-occupied property in 2021 – of which 2.7 million live in a detached house. Since the first spade of earth was turned in the suburbs, Danes have also got access to a much broader range of loan types at the banks and mortgage credit institutions. Interest rates may be fixed or variable, and interest-only payments can extend all the way up to 30 years.

The yellow bricks of the houses look as they always have, but they can be financed in many different ways compared to earlier – and that gives house hunters and homeowners new opportunities to select a loan that exactly fits their finances and needs.

Sources and expert

Prepared with professional sparring from Curt Liliegreen, Project Director at the Knowledge Centre for Housing Economics, and otherwise based on these primary sources: Arbejdermuseet.dk , Danmarkshistorien.dk and Finansdanmark.dk