Not everyone knows what job their great-great-grandfather had 150 years ago. However, for the Ewers brothers in Sønderborg, their history is not in doubt. The family has been running a company that supplies grain and feed to Danish farms for five generations.

Landmandsbanken (‘the Farmers’ Bank’) and later Danske Bank has been a key partner over the years. As Claus Ewers says: “Just as it is very important to be close to your customers, it is extremely important to be close to your bank.”

Landmandsbanken (‘the Farmers’ Bank’) and later Danske Bank has been a key partner over the years. As Claus Ewers says: “Just as it is very important to be close to your customers, it is extremely important to be close to your bank.”

b1ca7395-00090258-f61898ae

Nowadays, agriculture is not just about being good at growing crops or raising livestock. The modern farmer also has to be a skilled manager and have their finger on the pulse while constantly being ready to adjust to new needs and requirements, such as the transition to greener and more sustainable production.

However, when the Ewers brothers’ great-great-grandfather started his business, just accessing capital to produce for others than yourself was a challenge. Back in 1871, the banks were not for farmers.

When the bank moved out of town

By 1871, Frederik III’s ramparts had separated Copenhagen from the rest of the country for nearly 200 years. Life outside the capital contrasted starkly with the opportunities the city dwellers had – also when it came to your financial options.

Denmark had 18 banks. Only two were large banks, and both were located in Copenhagen. The 16 small banks did not have sufficient funds to be able to adequately support agriculture – and the two large banks could not see any potential in having farmers as customers. If a farmer wished to borrow money, then a citizen of Copenhagen’s name had to appear on the loan agreement, so farmers had to pay an additional fee to get a Copenhagen signature on the loan document.

However, that attitude to farmers was something a circle of the leading wholesalers and manufacturers of the day held no truck with.

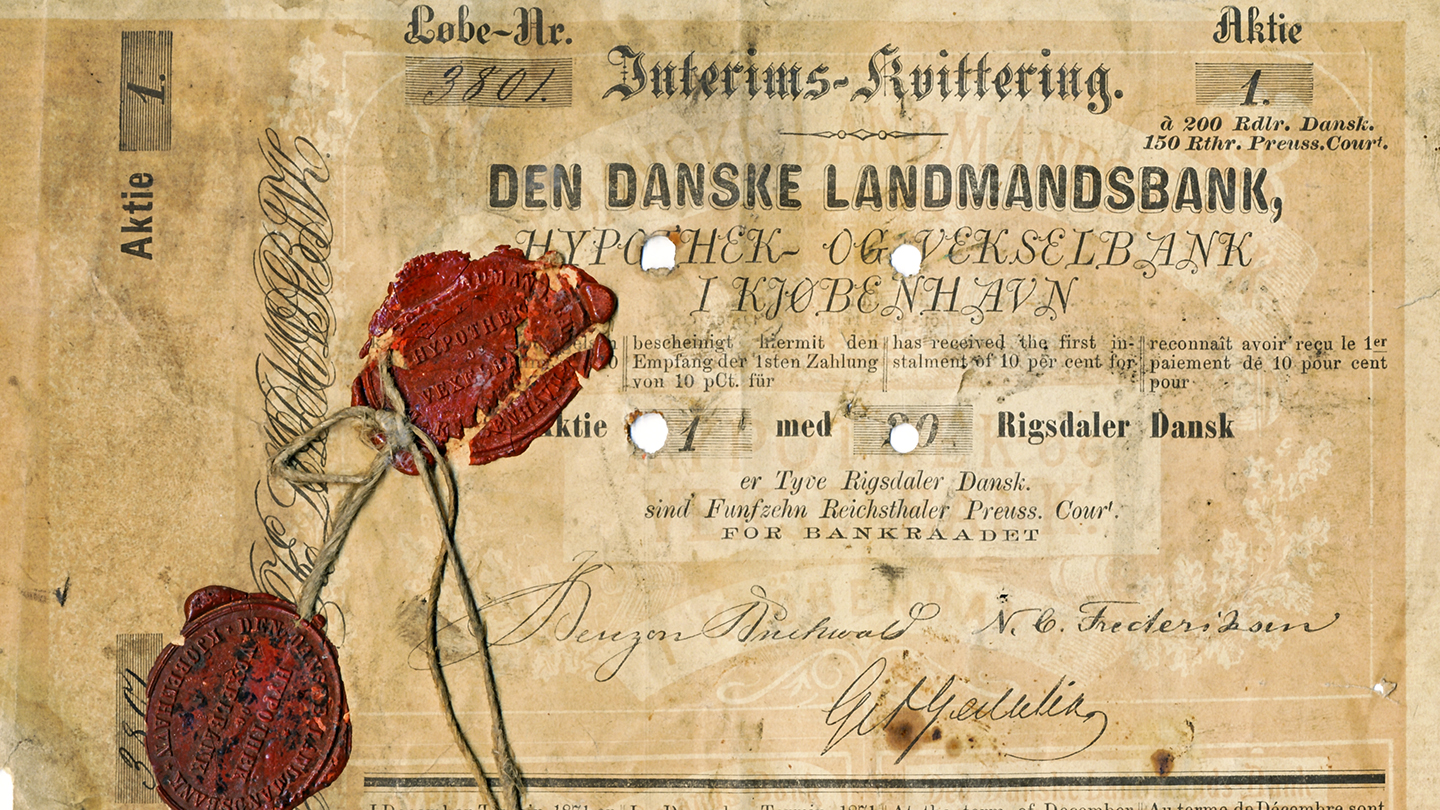

Therefore, on 5 October 1871, they founded a new bank that aimed to provide farmers with better opportunities to finance production. The bank was established with an equity of 2.4 million ‘rigsdaler’ (about DKK 5 million at the time), which was more than the 16 provincial banks combined. The bank was called Den Danske Landmandsbank, Hypothek and Vexelbank in Copenhagen – but was popularly known as just Landmandsbanken.

More than 100 years later, the bank changed name in 1976 to Den Danske Bank, which better reflected the bank’s nationwide presence and that it had customers from all sections of Danish society.

Photo: Saddle maker Gottlieb Hartvig Abrahamsson Gedalia founds Landmandsbanken, which was headquartered at Holmens Kanal in København, as can be seen in the photo.

Photo: The first share certificate for Landmandsbanken in 1886.

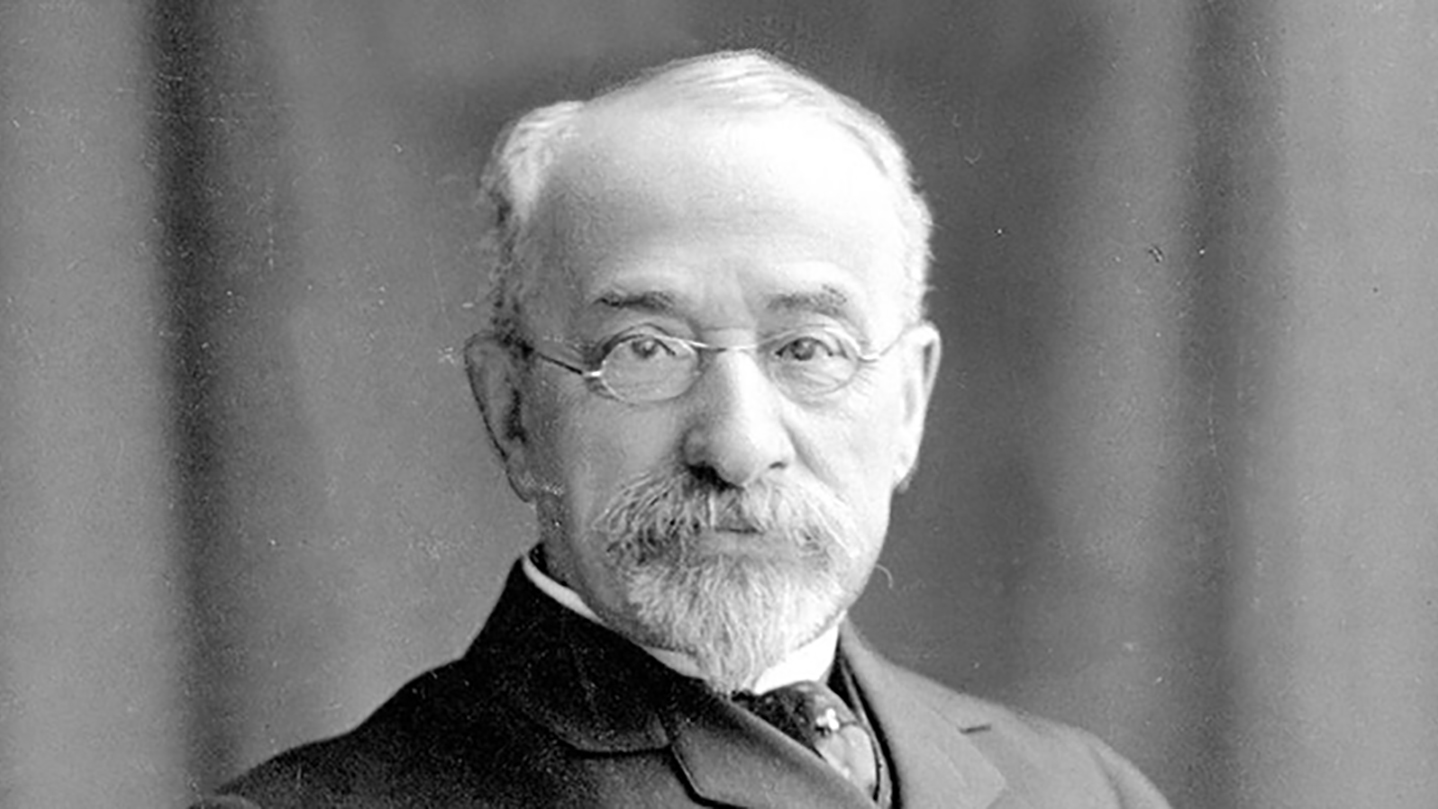

Photo: Isak Glückstadt was CEO of Landmandsbanken from 1872 until his death in 1910. He was succeeded by his son, Emil Glückstadt, who was at the helm when the bank went under in 1922.

Right from the start, the new bank stood out from the competition.

Landmandsbanken’s customers could have an overdraft, and in its very first year the bank opened four branches and four offices around the country outside Copenhagen’s ramparts. Thus it became the first Copenhagen bank to move out of the city and afford the rest of Denmark direct access to the Copenhagen capital market.

British appetites spur cooperatives

The farmers’ access to the city’s capital markets coincided with a sharp decline in international grain prices. This forced the Danish farmers to restructure their exports, with the UK rousing particular interest as a potential export market. Free trade and the UK’s huge appetite for butter, bacon and eggs made the market attractive for Danish farmers, who could supply dairy and meat products of high quality at a good price.

The UK’s growing appetite and demand fuelled Danish agricultural production, and suddenly there was a need for capital to make operations more efficient. The solution was the invention of a distinctive and characteristic constellation in Danish business: Cooperative societies.

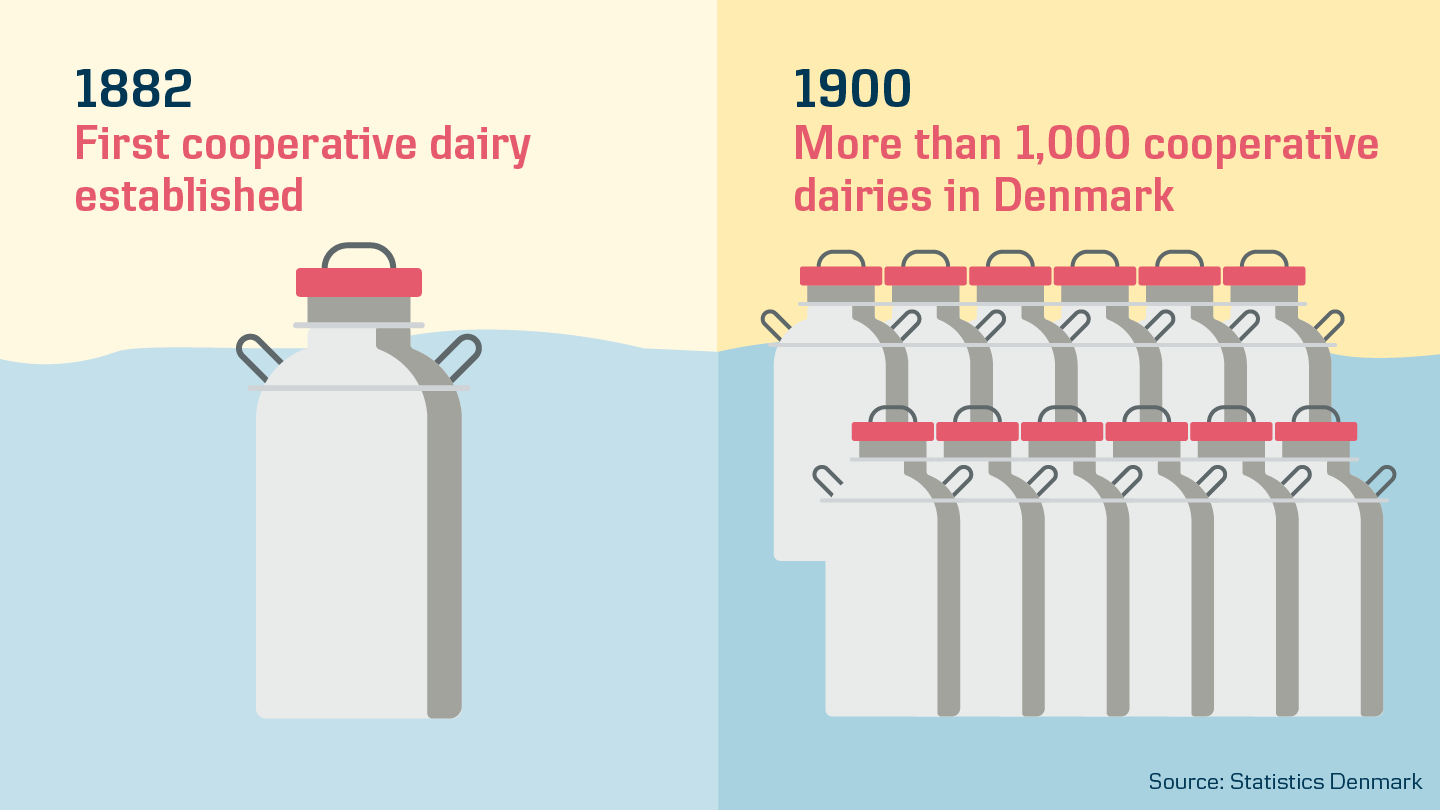

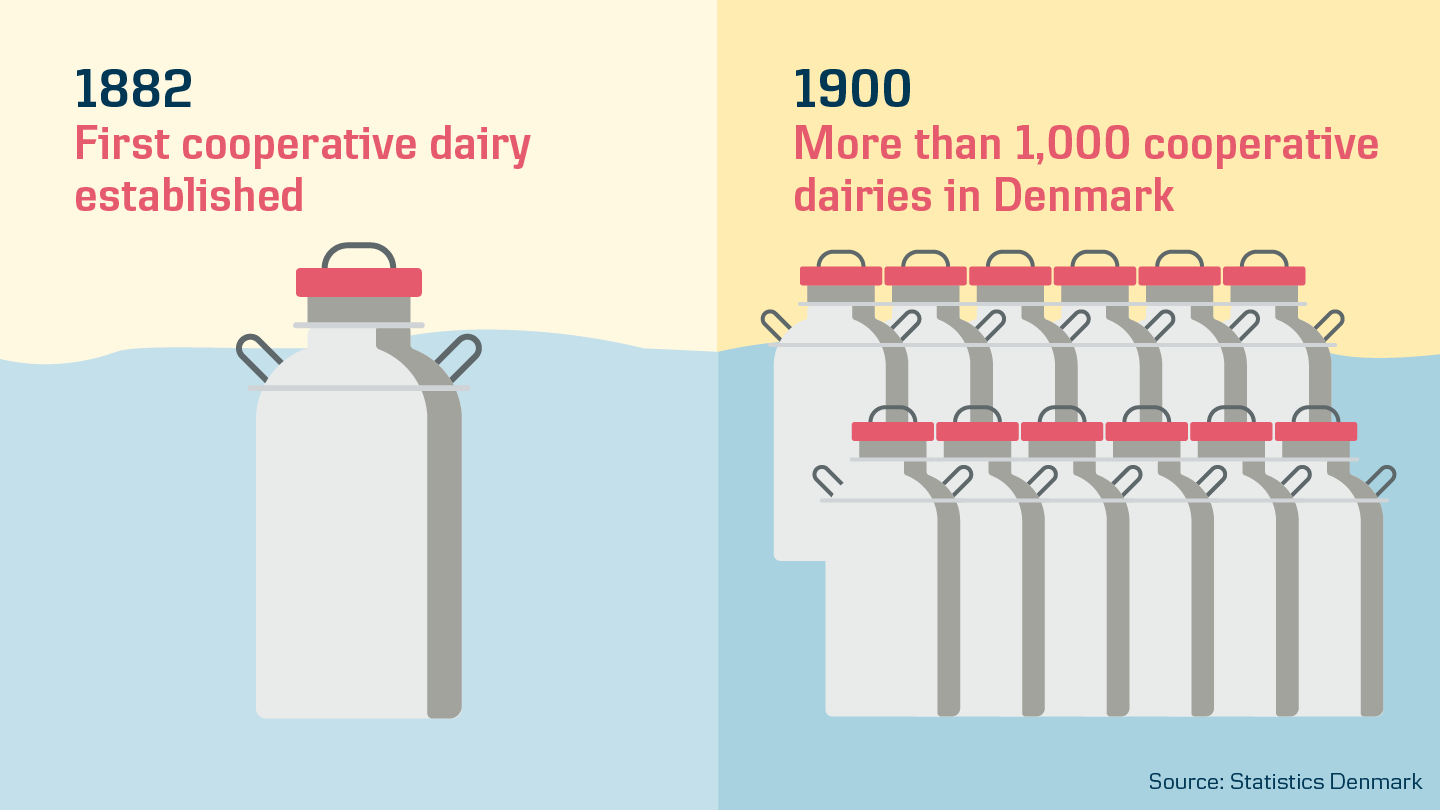

In 1882, a number of dairy farmers joined forces for purchasing, machinery sharing, livestock breeding and much more. The trend quickly took off. Just 18 years later, there were more than 1,000 dairy cooperatives across the country.

Landmandsbanken’s customers could have an overdraft, and in its very first year the bank opened four branches and four offices around the country outside Copenhagen’s ramparts. Thus it became the first Copenhagen bank to move out of the city and afford the rest of Denmark direct access to the Copenhagen capital market.

British appetites spur cooperatives

The farmers’ access to the city’s capital markets coincided with a sharp decline in international grain prices. This forced the Danish farmers to restructure their exports, with the UK rousing particular interest as a potential export market. Free trade and the UK’s huge appetite for butter, bacon and eggs made the market attractive for Danish farmers, who could supply dairy and meat products of high quality at a good price.

The UK’s growing appetite and demand fuelled Danish agricultural production, and suddenly there was a need for capital to make operations more efficient. The solution was the invention of a distinctive and characteristic constellation in Danish business: Cooperative societies.

In 1882, a number of dairy farmers joined forces for purchasing, machinery sharing, livestock breeding and much more. The trend quickly took off. Just 18 years later, there were more than 1,000 dairy cooperatives across the country.

Opportunities of scale

The cooperatives boosted efficiency, as the farms could produce more when part of a larger undertaking. Increased earnings from improved production also meant the farmers could invest in equipment that further increased productivity.

Hence, the farmers eventually accounted for the bulk of the country’s earnings and as a sector agriculture became critical to Denmark’s economy at the start of the 20th century.

“The cooperatives provided the potential to make something bigger than would have been produced if everyone worked independently,” explains Professor Paul Sharp from the University of Southern Denmark (SDU) here.

Hence, the farmers eventually accounted for the bulk of the country’s earnings and as a sector agriculture became critical to Denmark’s economy at the start of the 20th century.

“The cooperatives provided the potential to make something bigger than would have been produced if everyone worked independently,” explains Professor Paul Sharp from the University of Southern Denmark (SDU) here.

Modernisation of agriculture

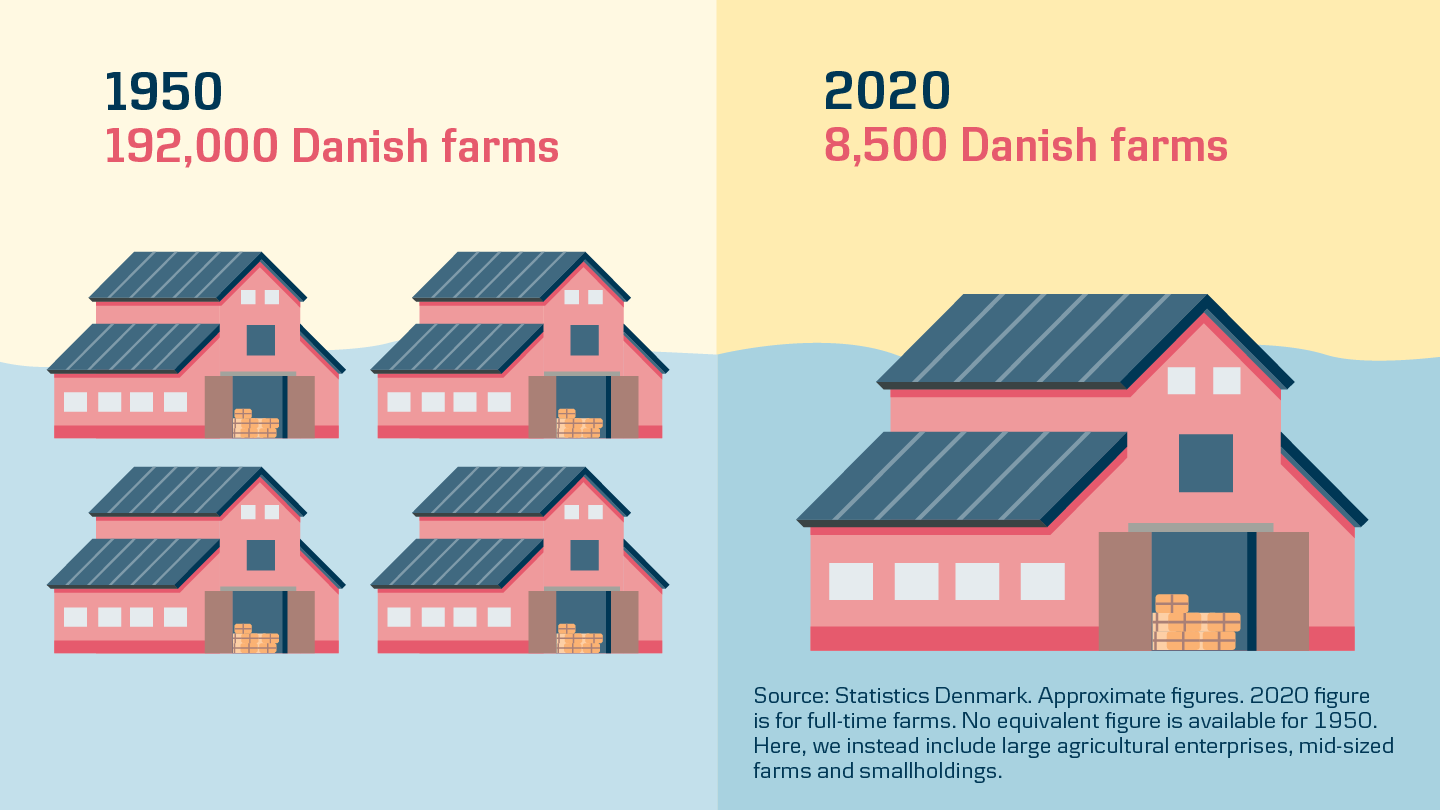

If we wind forward a little in Denmark’s history, we can see Danish agriculture take a huge leap forward when the tractor comes to Denmark just after World War II. Farms became fewer, but larger. They shifted even more from being family-run operations to professional businesses, and those that fared best bought up land and grew into mid-sized companies with a number of employees.

That picture still holds true today, and it makes ever greater demands on farmers and not least the capital required if you want to acquire a farm.

The many changes to production over the years have required investment, loans and new solutions, such as agricultural leasing and financial advisory services – just as in the Ewers Brothers case. In recent years, the sustainability agenda has had a massive impact on agriculture, just as it has on the industrial sector around the world.

In 2020, there were 8,500 full-time farms operating in Denmark – most of them were, and are, specialised in order to be able to compete on the international food market.

A good example of specialised production that at the same time attempts to solve some of the world’s major challenges, is so-called vertical farming. Here, producers cultivate food in vertically stacked layers independent of soil and weather. This makes it possible to grow crops in cities, and potential sustainability benefits include the food not needing to be transported very far to reach consumers. Furthermore, the solution offers the opportunity to produce more as world populations grow.

Vertical farming marks a dramatic change in farming compared to when the Ewers brothers’ great-great-grandfather started the family business in the 1800s. Likewise, there has been a dramatic change in the needs of society and business.

Just as Landmandsbanken invested in the transformation of agriculture 150 years ago, Danske Bank is now contributing to sustainable growth for future generations by, for example, supporting companies with tools, advice and funding.

And Ewers Brothers – they are still customers of the bank and are now a major export company with annual revenues in the billions.

Photo: 1890s. Farm in Mellerup. The mill in the background pumped water up for the family’s household needs.

Photo: 1950s. Arable farm in Tikøb. Farmer harvesting grain with a self-binder attached to the popular Ferguson tractor, which came to Denmark in connection with the Marshal Plan.

Photo: 2021. Nordic Harvest’s production hall. Nordic Harvest is one of the world’s largest vertical farms and is located at Grønttorvet, close to Copenhagen. 14 layers of lettuces and herbs are cultivated – sustainably and without crop sprays.

Sources and expert

Prepared with professional sparring from Professor in economic history, Paul Sharp, University of Southern Denmark, and Claus and Hans Otto Ewers, and also based on these primary sources: Landbohistorisk tidsskrift, Danmarkshistorien.dk and Tidsskrift for landøkonomi.